A huge part of our job as educators is to instill a healthy sense of identity in our students. This results in higher self-esteem and engagement in academic content as well as activities outside of school. We do this by helping students build skills that support an exploratory orientation to their relationship with self, and providing stability during a growth process that can be scary and threatening for many. This sense of threat is heightened when students are labeled with learning differences like dyslexia or dyscalculia, mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety, or conditions that present as both such as bipolar disorder or ADHD. This is particularly relevant for discussions on identity because a person is met with the fact that they are different from those around them, and they must explore what this means, or they risk identity confusion and low self-esteem. Unfortunately, many of these conditions are stigmatized and students may get bullied for their differences.

Assessment and Diagnosis

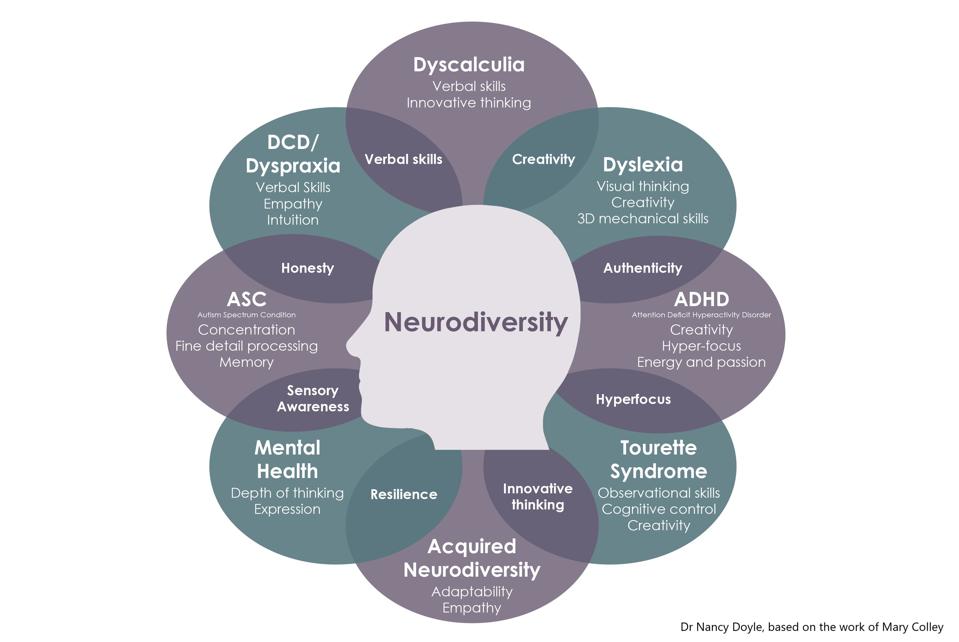

The first step to helping a student through this process is for the school community to be proactive in looking for learning differences and providing testing for students when available. Once diagnosed by an educational psychologist, or in some cases a doctor, students are now faced with a new reality. They need to explore what this means, not just in their relationship with themselves, but also how others may view them as a result of this new label. Unfortunately the diagnostic criteria for these conditions focuses on deficits and disabilities, when in fact every neurodivergent condition has well-documented positive traits associated with it. Rather than deficits, they are really differences in the way the brain processes information and expresses its energy and attention. One amazing movement in educational and mental health fields is Neurodiversity. It focuses on providing solidarity and positive identity development once a child is labeled as different. A brief overview of some strengths can be seen in the image below.

Exploration Facilitates Acceptance

Acceptance is a difficult task when many of these conditions carry negative stigma. The first task as an educator is to do a bit of research yourself to understand the positive aspects of the child’s learning difference and be able to recognize these skills and behaviors when they manifest in your classroom. Praising a student with dyslexia for their visual thinking and creativity on a regular basis reinforces to the child that their differences are also strengths and it will allow them to understand how they can provide a unique value in educational and social circles now and into the future. You can also go a step beyond and provide opportunities for them to explore their condition in depth. The British Dyslexia Association has excellent resources on Teaching for Neurodiversity.

In addition, a student recently diagnosed with dyslexia will benefit tremendously from completing a supervised project where they research the condition from a neurodiversity perspective, including the history and development of the construct, it’s associated challenges, strengths, and patterns, and the many famous dyslexic people who are leaders in industries because their dyslexia actually gives them a competitive advantage in certain environments. The key component of such a project will be for the student to connect it to specific examples in their life and provide a narrative understanding of their past and present. In doing so, they can visualize their future. Ultimately the student will decide the extent to which this condition is “a part of them” versus “something they have.”

Identity First or Person First Language?

The key question for students (not the adults in their life) to answer after being diagnosed with a learning difference or mental health condition is: “Is this a part of my identity or not?” If we continue with the example of dyslexia, one can notice a difference between saying “I am dyslexic,” which is identity-first language, vs “I have dyslexia,” which is person-first language. If, through exploration, a student finds that dyslexia affects them significantly in educational and social situations and that they can really identify with the challenges as well as strengths, then they may be more inclined to make it a part of their identity and seek out accounts on social media where other dyslexics are posting about their life. This solidarity is paramount in the face of bullying. If the student feels that dyslexia is not a part of who they are deep down, but rather is something external to themselves that they grapple with, they will likely be inclined to use person-first language and choose not to be seen through this lens. As educators we must be sensitive to these distinctions. We are agents of identity formation and it is the micro-interactions where identities are constructed. Since adolescents are really conscious of perspective taking and point-of-view for the first time, they are hyper aware of how others see them. One last thing to think about as we guide students through this important process is their identity processing style as laid out by developmental psychologist Michael Berzonsky. I have provided definitions below with some things to think about as you observe your students in this context.

Identity Processing Styles

Watch your students grapple with these labels, and keep in mind the following styles:

- Informational – Student seeks out identity relevant information and is open to new ideas. They are able to suspend judgement while processing and evaluating how this identity makes them think and feel.

- If a student can take this approach, it is ideal. The stigma and uncertainty can make it very challenging to explore with suspended judgement, so a teacher can really provide support in that area.

- Normative – Student is not comfortable with uncertainty and internalizes the values and identities that are prescribed from their environment and significant others without much exploration.

- These students may be eager to make a commitment to an identity but very hesitant to explore. It’s all very stressful and they just want to “get it over with.” This is risky because a student may construct their identity around a condition before actually understanding the implications. They may make their decision based on whether it is “cool” or not to have the condition. Encouraging true exploration is key for these students.

- Diffuse-Avoidant – The student is very reluctant to confront identity conflicts/issues. Their actions and choices tend to be determined by situational demands.

- In this situation, a student prefers not to deal with the issue at all until they are forced to. With learning differences, this is a big risk because they may not advocate for themselves and receive necessary accommodations. With social differences, this could lead to lower self-esteem due to going unseen. As educators we need to find a balance where we understand the student’s trepidation and “force the issue” in a non-threatening manner.

It is my passion to spread knowledge about healthy identity development to educators and their students. I consult with schools and teachers to help them implement structures and pedagogy that promotes an exploratory orientation to identity during the crucial stage of adolescence. Please don’t hesitate to reach out if you are interested in implementing trainings in your school around identity development or helping your students explore the relationship between their learning or social differences and their identity as I’ve described in this post. I can be reached at Greg@adaptiveedgecoaching.com