We are all different. No one disputes that. We come in different colors, shapes, and sizes. We express ourselves in different ways as well. Some people love to talk, others enjoy painting, some like to write, and others love to sit alone. One of the biggest things we express as humans are emotions. In our day to day lives, we watch people cry, scream, laugh, smile, yell, frown, and relax. We can visually see people experiencing their range of emotions as they express them. We also recognize that not everyone shows their emotions in the same way; what might make me cry may make you yell or what makes me smile may make you laugh.

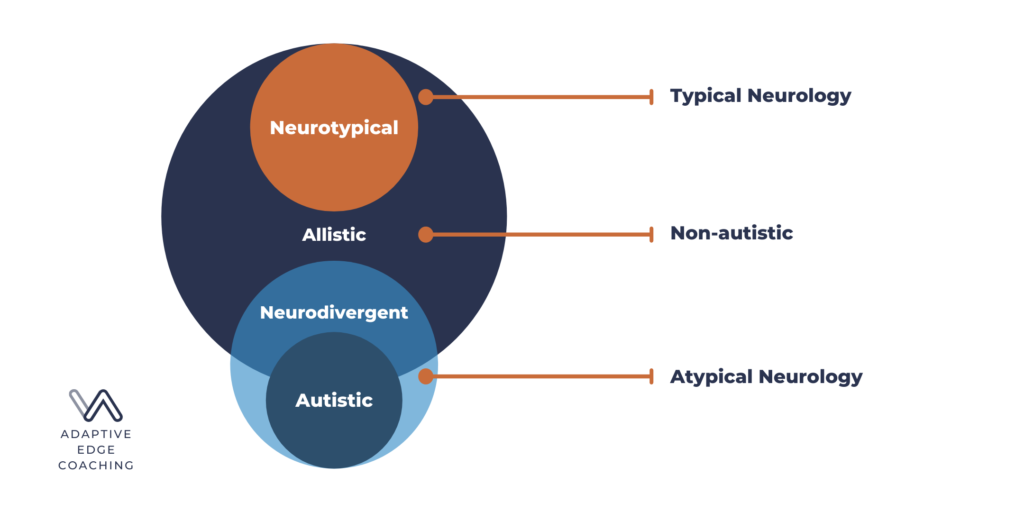

What we might not consider is how neurodivergent people express their emotions and their identity. What does it mean to be neurodivergent? It means that according to psychological standards, a person does not fit the norms created. Being neurodivergent can include learning differences like dyslexia or dyscalculia, mental health issues like anxiety or depression, and other conditions like autism, ADHD, or Tourette’s syndrome.

Emotions are constructs. Since they are constructed socially and individually, everyone can experience or present them in different ways. This applies to neurodivergent people as well. With regards to people with autism, some claim that they do not feel empathy or emotion. This notion is entirely false. Lisa Feldman Barrett’s research on constructed emotions is a great ally for people with autism. When referring to emotions as concepts rather than innate abilities, we allow for an understanding that neurodivergent people might not understand the concepts of emotions that are created in the same way that neurotypical people do. This eliminates the notion that they simply do not understand emotion at all.

Barrett’s theory explains that there is no universal expression of emotion. That is outdated science. Research has shown that although we think we can look at someone’s face and determine their emotion, we cannot. All we are doing by looking at someone’s facial expressions and trying to determine emotion is measuring culture since emotions are socially constructed. Affective computing is a new field of artificial intelligence that is trying to develop software that can determine emotions by scanning a person’s facial expressions and body language. While facial expressions and body language are useful communication tools, they do NOT indicate emotion with consistent accuracy. They only indicate the culturally dominant form of expression. Big technology companies like Amazon and Facebook are looking to adopt this technology, but it is not supported by neuroscience. This is also very dangerous because it will discriminate against marginalized people like those with autism or people from minority/foreign cultures who express their emotions differently.

As you have previously seen in this series on emotion, emotion is constructed and requires an understanding of the culture and society in which it was produced. The prolific autistic scholar Damian Milton coined the concept of the “double empathy problem.” This double empathy problem explains the idea that empathy is a two-way street. If I express to my friend that I am sad and she does not understand it, I cannot correctly assume that she does not understand emotion and my way is the correct way. This disconnect translates to individuals with autism as well. Neurotypical people might have difficulty understanding neurodivergent people’s expressions because they experience different cultural and societal influences. It does not mean that one way is right and the other is wrong. Although this misunderstanding goes both ways, it disproportionately affects the neurodivergent minority. When we misinterpret signs from someone with autism or ADHD, we can unintentionally stigmatize their expressions, or assume that ours are “correct,” when in reality this is simply a difference.

Let’s further explore this double empathy problem with an example. AutSciPerson on Twitter gives an example that “I may laugh because I’m trying to get through the pain a crying baby is causing me. It doesn’t “bring me joy.” This illustrates that laughing does not always equate to happiness like a neurotypical person might assume. Laughter can also express discomfort. It is important to remember that everyone’s emotions are sincere, we just might not have the key to understand them. This does not mean that the key does not exist. We just need to find it!

If you are interested in learning more about emotions, empathy, and neurodiversity, contact Greg Murray at greg@adaptiveedgecoaching.com for a consultation.